Rap History of the World © by Philip Day

Contact: Twitter @PhilipDayUKRHW is going to Camden Fringe 2019!

5th, 12th and 16th August 6.45pm

Click here for tickets

Tickets: https://camdenfringe.com/show.php?acts_id=2641

Welcome to the Rap History of the World! Check out the videos here for Act I Parts I and II... scroll down for a longer introduction, the full lyrics and commentary notes. Enjoy!

About - Contents (full lyrics) - Disease Lesson - IBHA 2016 Presentation (27Mb pptx) - Teaching Notes: Act I, Act II, Act III - Feedback

Act I Part I - The Physical Universe

Act I Part II - Life and Evolution

Introduction

Act I starts with the Big Bang and (very briefly) narrates a few developments in the physical universe before charting major milestones and trends in the emergence and evolution of biological life, and then human evolution down to the Neolithic.

Act II, covers pre-industrial 'civilized' history: the emergence of agriculture and the first states and civilizations, and themes in their histories, including interaction and exchange, ecological influences, demographic cycles and the role disease.

Act III explores various aspects of the 'modern revolutions' since c.1500 AD, including the 'rise of the West' and reactions and internal turmoil generated by it among the rest of the world, until the recent re-balancing of global power, and finally a brief survey of problems and opportunities in the world today.

You can click on the symbols to reveal commentary notes (click again to close). The typical purpose of these is to point you to the works of the various authors who have inspired the particular argument. Occasionally they digress on a tangent about some theory of mine, or elaborate or add a point of information to the verse. However in general they will not explain what the rap is trying to say, nor reveal subtle allusions - that would spoil all your fun!

The RHW itself was written May-July 2013, and this website including pictures and commentary notes were completed in September 2013. Thanks to UX guru Fraser Deans for technical assistance.

The original inspiration for this project came from watching Baba Brinkman's highly entertaining and award-winning live show, The Rap Guide to Evolution, which I saw in London in 2010.

Feedback is very welcome - there is a form here, or email the author on contact@raphistoryoftheworld.com.

Finally, I would like to thank all the image owners who kindly gave their permission to use their images here, and also those who donated their images to the Creative Commons.

Enjoy!

Philip Day

London, 2013

Contents

(Click these links or keep scrolling for lyrics...)Act I - The Physical Universe, Life and Human Evolution

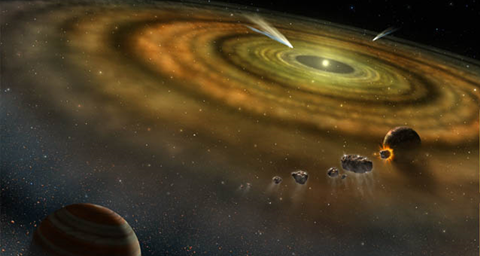

The Early Universe

Gravity, Stars and Planets

The Origin of Life

Gaia Theory

The Eukaryote and Macroscopic Life

Reflections on the Evolutionary Process

Human Evolution - Divergence

Human Evolution - Genus Homo

Hunter Gatherers

Act II - Agriculture and Civilizations

Agricultural Revolution

The Human Web

Macroparasites and Civilization

Cultural Achievements

Religion

Recurrent Collapse

Demographic Cycles

Ecological Catastrophe

Disease

Act III - World History since 1500, inc Scientific and Industrial Revolutions

The Rise of the West

The Age of Discovery

The Columbian Exchange

The Scientific Revolution

The Industrial Revolution

European Expansion and Response

Enlightenment

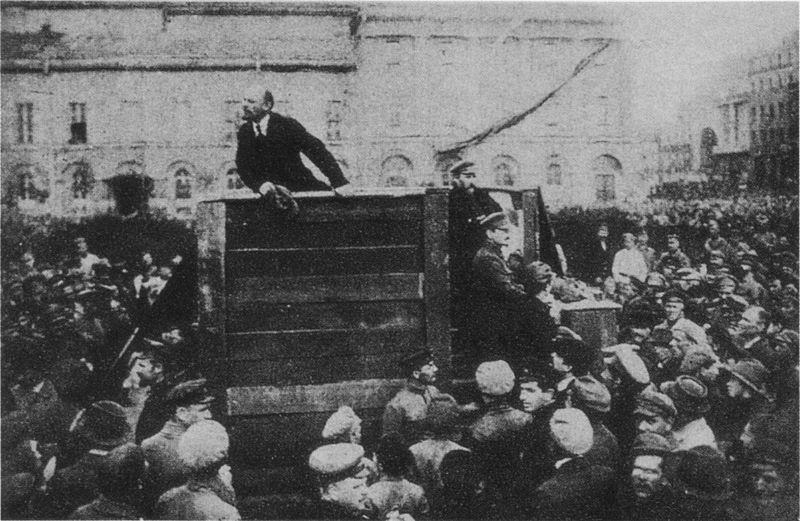

Communism

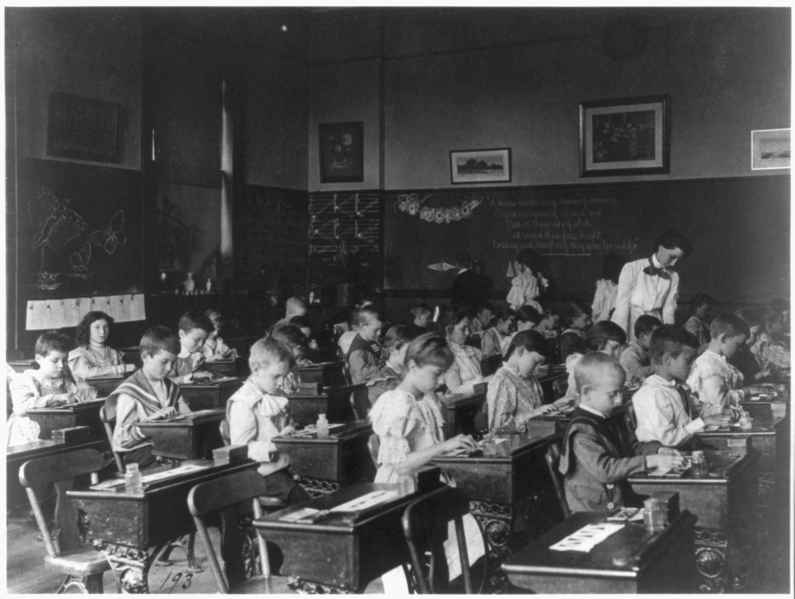

State Building and Nationalism

20th Century Climax

The World Today: Problems and Opportunities

Commentary notes will appear in these bubbles.

Click on the ? again to close.

Click on the ? again to close.

Act I - Evolution: Physical, Chemical, Biological, Human from the Big Bang to the Neolithic

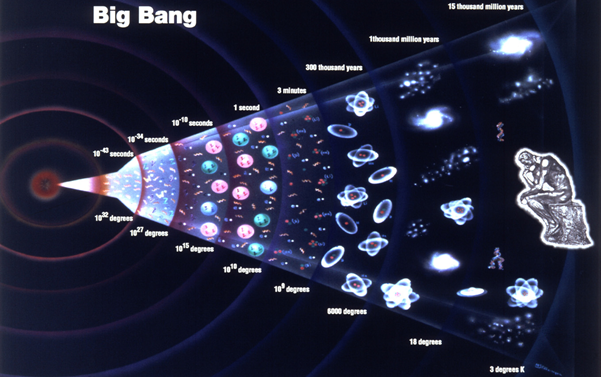

Big Bang

Where it all began

Deep time

Beyond imagination

First pure radiation

That expanded and stretched

Cooled and condensed

Get prepared

For E=mc2

Photons became protons

Add electrons

We got hydrogen

The atomic spark

But, most matter is Dark…

Where it all began

Deep time

Beyond imagination

First pure radiation

That expanded and stretched

Cooled and condensed

Get prepared

For E=mc2

Photons became protons

Add electrons

We got hydrogen

The atomic spark

But, most matter is Dark…

The Rap History of the World could be read as a history of the Universe, or of the World, or of Humans, or equally as a history of gamma rays (high-energy light rays).

Early in the universe there were only gamma rays, which later (after 10-24 seconds!) cooled and turned into protons and other particles, which later formed atoms, which… and so on. Arguably we are the descendants of a big fireball of gamma rays, and we are one thread of the story of what happened to them.

Early in the universe there were only gamma rays, which later (after 10-24 seconds!) cooled and turned into protons and other particles, which later formed atoms, which… and so on. Arguably we are the descendants of a big fireball of gamma rays, and we are one thread of the story of what happened to them.

Dark matter is matter which interacts with 'normal' (baryonic) matter through gravity, but does not absorb or emit electromagnetic radiation, therefore we cannot observe it directly with any telescope. It is estimated to constitute 85% of all matter.

There is also dark energy, which physicists tell us constitutes 68% of the total mass-energy of the universe (mass and energy are interchangeable phenomena), but this is beyond the RHW.

Chaisson and Christian (see next note) both offer concise treatments of evolution in the physical universe, including the topics mentioned in these verses; I recently took Hitoshi Murayama's coursera course From the Big Bang to Dark Energy as a refresher. Wikipedia is also very good on these subjects.

There is also dark energy, which physicists tell us constitutes 68% of the total mass-energy of the universe (mass and energy are interchangeable phenomena), but this is beyond the RHW.

Chaisson and Christian (see next note) both offer concise treatments of evolution in the physical universe, including the topics mentioned in these verses; I recently took Hitoshi Murayama's coursera course From the Big Bang to Dark Energy as a refresher. Wikipedia is also very good on these subjects.

And even if we can't see

We can feel it's gravity,

The key to galaxies

Spinning with obscene speed:

100 billion stretching far,

Each, 100 billion stars

Gravity is the central organising concept of David Christian's Maps of Time (2004), whereas Eric Chaisson's focus is on energy flow density, in Cosmic Evolution (2001).

These two great works are mutually-consistent 'theories of everything' from the Big Bang to the present day and both are important influences of the RHW. More on each below…

These two great works are mutually-consistent 'theories of everything' from the Big Bang to the present day and both are important influences of the RHW. More on each below…

Now gravity attracts

Anything with mass

Like clouds, of dust and gas

That shrink, until at last

Getting denser under pressure

Raise the temperature

Great engines ignite

Nuclear fusion makes bright

The dark night

Let there be light!

Anything with mass

Like clouds, of dust and gas

That shrink, until at last

Getting denser under pressure

Raise the temperature

Great engines ignite

Nuclear fusion makes bright

The dark night

Let there be light!

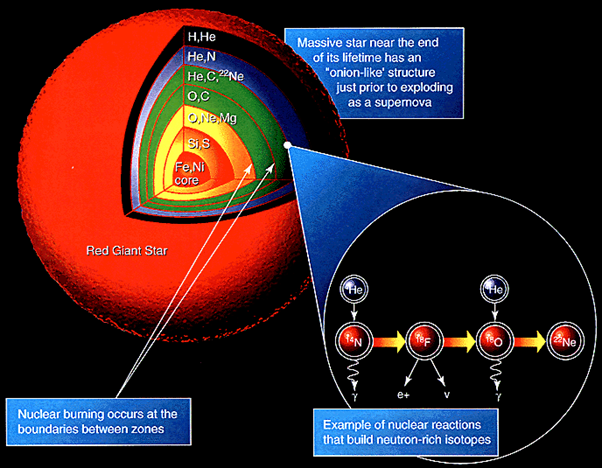

First hydrogen to helium

Then boron and carbon,

Nitrogen and oxygen,

And on and on…

The ancient stable

Of the periodic table

Everything you touch

Everything you own

Everything in you

If you ask where it begun

It was in the heart

Of a long dead sun

Then boron and carbon,

Nitrogen and oxygen,

And on and on…

The ancient stable

Of the periodic table

Everything you touch

Everything you own

Everything in you

If you ask where it begun

It was in the heart

Of a long dead sun

And when a supernova flashes

Scattering the ashes

The next generation of stars

Can have planets, like Mars

And with the perfect size and distance

- The Goldilocks Conditions -

Maybe there'd be water, for an instant…

Scattering the ashes

The next generation of stars

Can have planets, like Mars

And with the perfect size and distance

- The Goldilocks Conditions -

Maybe there'd be water, for an instant…

And so it came to be

That on one of these,

Amid the primal seas

A dash of energy

Linked C-H-N-O-S and P

Making:

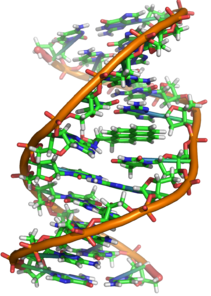

Amino acids, RNA, DNA

The base of everything alive today

That on one of these,

Amid the primal seas

A dash of energy

Linked C-H-N-O-S and P

Making:

Amino acids, RNA, DNA

The base of everything alive today

'Dash' evokes lightning, and amino acids have indeed been created in laboratory conditions by passing electrical current through a 'primordial soup' of water, methane, ammonia and hydrogen as early as in 1953 (the Miller-Urey experiment).

However, latest thinking is that life originated at thermal vents on the ocean floor. The most confident exposition I have read, by Nick Lane, is that life's origin was at mid-ocean alkali vents (as opposed to central-ocean ridge acidic vents) - Nick Lane, Life Ascending: The Ten Great Inventions of Evolution (2009).

However, latest thinking is that life originated at thermal vents on the ocean floor. The most confident exposition I have read, by Nick Lane, is that life's origin was at mid-ocean alkali vents (as opposed to central-ocean ridge acidic vents) - Nick Lane, Life Ascending: The Ten Great Inventions of Evolution (2009).

Trapped in a membrane

Forming long chains

Information store

And self-replicator

Mutate, replicate:

Innovations can accumulate

At a rate that fascinates

Forming long chains

Information store

And self-replicator

Mutate, replicate:

Innovations can accumulate

At a rate that fascinates

Diversification

Follows descent with modification

And non-random elimination

Of all but the best adapted

I just rapped that

'Descent with modification' was a phrase used by Charles Darwin in The Origin of the Species (1859), along with 'natural selection' to describe what was later termed 'evolution'.

Producers and consumers

Symbiotic communities

Tectonics cycling minerals

With life building chemicals,

Forming

Mechanisms of feedback,

A global thermostat

That began to stabilise

What's in the seas and skies

And gave rise

To the blue marble that we marvel at

Lovelock called it Gaia,

These rhymes are on fire!

Symbiotic communities

Tectonics cycling minerals

With life building chemicals,

Forming

Mechanisms of feedback,

A global thermostat

That began to stabilise

What's in the seas and skies

And gave rise

To the blue marble that we marvel at

Lovelock called it Gaia,

These rhymes are on fire!

Geerat Vermeij, Nature: An Economic History (2004) is a fantastic analysis of economic forces in natural history. Beyond the line 'Producers and consumers' here, and another reference below, I unfortunately did not have enough space to present Vermeij's many rich ideas any further, but would highly recommend this book.

See note about Lynn Margulis and symbiosis in the next verse.

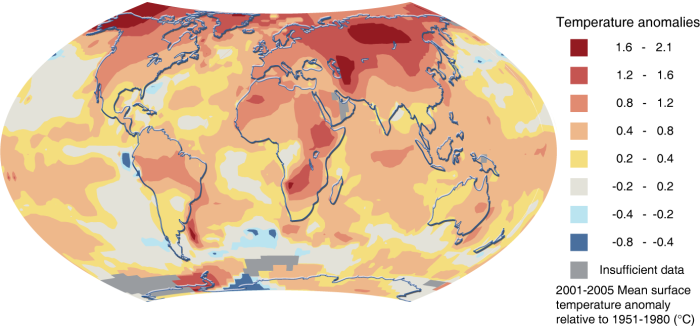

James Lovelock is a famous scientist who first postulated the Gaia Hypothesis (now Gaia Theory) in 1965; Lynn Margulis helped develop it in the 1970s. Gaia Theory states that interacting biological, chemical and physical processes formed multiple, linked feedback loops which stabilise the contents and temperatures of the atmosphere and oceans at levels conducive to the existence of life. Such a phenomenon is known as homeostasis and is a common regulator in biological life, e.g. in cells or blood; for this reason, Gaia is said to resemble an organism. Discovering Gaia Theory c. 2004-5 was a mind-altering experience for me.

To give one example of how Gaia's mechanisms work, bacteria accelerate rock-weathering, which takes CO2 out of the atmosphere to form mineral carbonates, causing cooling. But bacteria metabolise more rapidly at higher temperatures, hence the feedback. This and other mechanisms have helped keep temperature in the stable range we are familiar with today, while the sun has increased its output c. 40% in 4 billion years, which 'should have' caused a c. 100°C rise in temperature. Similarly, in the oceans, organisms which build shells grow more rapidly at higher salt levels, lowering sea salt levels (and subsequently decreasing their own growth rates). Sea salt levels are c. 4%; Lovelock estimated that rivers' delivery of salts would saturate the oceans at c. 20% (far too saline for most life to exist) in only 80 million years.

The Gaia Hypothesis was originally rejected as anthropomorphic and teleological; the authors admit that it was wrong in its initial formation, but subsequent revisions have been more widely accepted. Most significantly, Gaia Theory has spawned entire fields of science which are in good health today, such as Earth Systems Science, Geophysics, etc. Criticism remains (most notably from Richard Dawkins), but seems misguided to me; when I first read Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth (1979), I thought Lovelock was explicitly clear that the concept of Gaia as an organism is just an analogy.

At the time of writing, James Lovelock is 94; he is the only living author directly mentioned in the Rap History of the World. For me there are interesting parallel between his career and that of William H. McNeill writing about human history (and also still going strong at 95): both attempted novel, macro-level approaches to their fields which identified global, enduring patterns with outstanding success from the 1960s onwards, while it took mainstream academia several decades (or more) to begin to accept and integrate their ideas.

To give one example of how Gaia's mechanisms work, bacteria accelerate rock-weathering, which takes CO2 out of the atmosphere to form mineral carbonates, causing cooling. But bacteria metabolise more rapidly at higher temperatures, hence the feedback. This and other mechanisms have helped keep temperature in the stable range we are familiar with today, while the sun has increased its output c. 40% in 4 billion years, which 'should have' caused a c. 100°C rise in temperature. Similarly, in the oceans, organisms which build shells grow more rapidly at higher salt levels, lowering sea salt levels (and subsequently decreasing their own growth rates). Sea salt levels are c. 4%; Lovelock estimated that rivers' delivery of salts would saturate the oceans at c. 20% (far too saline for most life to exist) in only 80 million years.

The Gaia Hypothesis was originally rejected as anthropomorphic and teleological; the authors admit that it was wrong in its initial formation, but subsequent revisions have been more widely accepted. Most significantly, Gaia Theory has spawned entire fields of science which are in good health today, such as Earth Systems Science, Geophysics, etc. Criticism remains (most notably from Richard Dawkins), but seems misguided to me; when I first read Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth (1979), I thought Lovelock was explicitly clear that the concept of Gaia as an organism is just an analogy.

At the time of writing, James Lovelock is 94; he is the only living author directly mentioned in the Rap History of the World. For me there are interesting parallel between his career and that of William H. McNeill writing about human history (and also still going strong at 95): both attempted novel, macro-level approaches to their fields which identified global, enduring patterns with outstanding success from the 1960s onwards, while it took mainstream academia several decades (or more) to begin to accept and integrate their ideas.

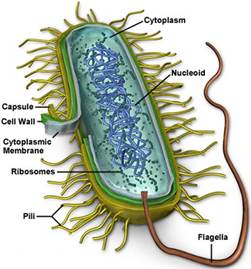

3 billion years

Of the single cell

They'd done well

But life went further:

When bacterial merger

Made the eukaryote

Of historical note

Horizons opened far

We're multi-cellular

Of the single cell

They'd done well

But life went further:

When bacterial merger

Made the eukaryote

Of historical note

Horizons opened far

We're multi-cellular

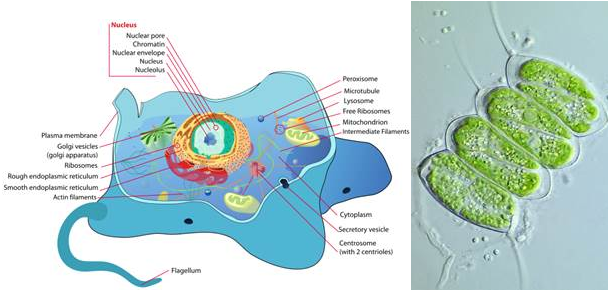

The eukaryotic cell is a much larger and more complex cell than a bacteria; all macroscopic, multi-cellular life is eukaryotic. Lynn Margulis first proposed bacterial merger as the origin of the eukaryote in 1966; eventually that theory was accepted as fact by biologists. She has written many works on this and other topics; the first I read was Symbiotic Planet: a New Look At Evolution (1998), which is engagingly written and raises powerful questions about the distinction between community and individual, and Acquiring Genomes (2002).

The history of biological evolution has had many excellent treatments; two I have enjoyed were Richard Fortey's Life: An Unauthorised Biography (1997) and Richard Dawkins' The Ancestor's Tale (2004).

About half a billion years ago…

Deep in the oceans

The Cambrian explosion

Set in motion

A great radiation

Of prey and predation

Things to help swim

Like fins and branching limbs

Teeth, claws, grasping jaws

Sensory perception

Evasion and deception

The arms race continues at pace

Forever. For ever?

For ever ever.

The Cambrian explosion

Set in motion

A great radiation

Of prey and predation

Things to help swim

Like fins and branching limbs

Teeth, claws, grasping jaws

Sensory perception

Evasion and deception

The arms race continues at pace

Forever. For ever?

For ever ever.

Simon Conway Morris' The Crucible of Creation (1998) is an enthusiastic survey of the middle-Cambrian world and the forces driving its evolution; we know it mainly from fossils discovered in the 'Burgess Shale' rocks in the Canadian Rockies, c. 500 million years old. The animals which dominated Cambrian ecosystems are very different in form to those which succeeded them in the fossil record.

Lately, the Chengjiang fauna from China, some 10 million years younger than the Burgess Shale, has risen in prominence.

Lately, the Chengjiang fauna from China, some 10 million years younger than the Burgess Shale, has risen in prominence.

Geerat Vermeij's Nature: An Economic History (2004), mentioned above, has, amongst lots of rich content, a particularly thorough section analysing techniques of resistance to predation.

Life passed with distinction

Five mega-extinctions

From without or within

The atmosphere is thin

Volcanic eruptions

Asteroid interruptions

Once or twice

Earth's been covered in ice

But after adversity

Comes fresh diversity

Other branches of the tree

Leading the recovery

Five mega-extinctions

From without or within

The atmosphere is thin

Volcanic eruptions

Asteroid interruptions

Once or twice

Earth's been covered in ice

But after adversity

Comes fresh diversity

Other branches of the tree

Leading the recovery

Tony Hallam's Catastrophes and Lesser Calamaties (2004) is a very concise survey of mass extinction episodes throughout biological history, and the available evidence in search of their causes. Multiple factors combined during these events and it is difficult to pick them apart in causal analysis; some of them are still subject to debate. Apart from anything else, these events were dramas of environmental change and cataclysm far beyond our imagination.

Doug Macdougall's Frozen Earth: The Once and Future Story of Ice Ages (2004) does what its title suggests well. The last 'Snowball Earth' event occurred c. 650 million years ago (mya), 'not long' before the first macroscopic soft-bodied fossils (c. 580 mya), and the 'Cambrian explosion' described above beginning c. 540 mya. It is possible, although not certain, that the Earth was completely covered in ice, and it may have happened 2 or even 3 times, or these may have been lesser (but still major) glaciations. There have of course been lots of other glaciations; these and the techniques and evidence used to study them are well-presented in Frozen Earth.

And so it came to be

That creatures of the sea

Ventured onto land

And would quickly expand

From amphibians to simians

And lots between we've seen

Colossal among the fossils

Are dinosaurs

Once ruled the world

Today they survive

Only as birds

While mammals rised late

To dominate

That creatures of the sea

Ventured onto land

And would quickly expand

From amphibians to simians

And lots between we've seen

Colossal among the fossils

Are dinosaurs

Once ruled the world

Today they survive

Only as birds

While mammals rised late

To dominate

Invertebrate animals first migrated onto land c. 450-500 mya, and verterbrates c. 350-300 mya.

We've seen the creation

From random generation

Of new entities, even whole environments

Driven by selection

Against the direction

Of entropy

So it grows: life's magic tree.

But is the point mutation

The Lord of all Creation

What about

Epigenetic methylation

Chromosome hybrids

Bacterial plasmids

A lot of what’s inside us

Got here by virus

So maybe part of the answer

Lies in horizontal gene transfer

And what’s this I’m hearing

Genomes rearranging

Is it natural and normal:

Genetic engineering?

Note the propensity

To increase complexity,

And energy-flow density:

Evolution can operate

On systems small and great

Particles, chemicals

Cells, plants and animals

The trends transcend

Different realms

Will they hold true

For human worlds too?

From random generation

Of new entities, even whole environments

Driven by selection

Against the direction

Of entropy

So it grows: life's magic tree.

But is the point mutation

The Lord of all Creation

What about

Epigenetic methylation

Chromosome hybrids

Bacterial plasmids

A lot of what’s inside us

Got here by virus

So maybe part of the answer

Lies in horizontal gene transfer

And what’s this I’m hearing

Genomes rearranging

Is it natural and normal:

Genetic engineering?

Note the propensity

To increase complexity,

And energy-flow density:

Evolution can operate

On systems small and great

Particles, chemicals

Cells, plants and animals

The trends transcend

Different realms

Will they hold true

For human worlds too?

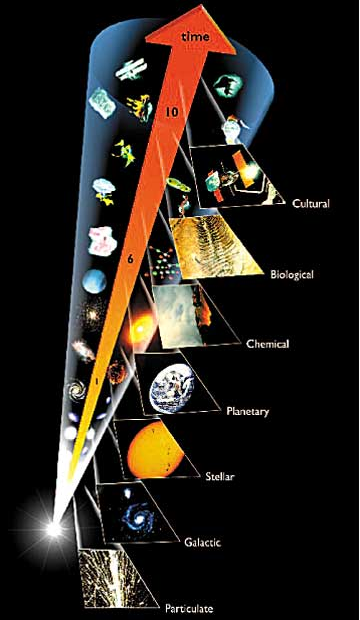

This is the central argument of Eric Chaisson's Cosmic Evolution (2001): that the rate of flow of energy per unit mass has tended to increase as new types of entity have evolved, which is closely linked to increasing complexity. The genius of this is Chaisson's success in comparing everything from galaxies to bacteria to jet engines using the same metric (with units of erg/s/g; an erg is a unit of energy equivalent to 10-7 joules, or 100 nano-joules).

Chaisson has another magnum opus which covers the same material in a more qualitative way: Epic of Evolution (2003) considers the different realms of evolution - particles, galaxies, stars, planets, chemicals, biological life, human societies, culture and technology - and is a slightly easier read than Cosmic Evolution.

Chaisson's own website gives an excellent concise introduction, including videos.

Chaisson has another magnum opus which covers the same material in a more qualitative way: Epic of Evolution (2003) considers the different realms of evolution - particles, galaxies, stars, planets, chemicals, biological life, human societies, culture and technology - and is a slightly easier read than Cosmic Evolution.

Chaisson's own website gives an excellent concise introduction, including videos.

Leonid Grinin, Andrey Korotayev, et al. edit a series of almanacs entitled Evolution, which began in 2011, discussing themes in macroevolution, i.e. a level of abstraction beyond biological life, considering evolution from the perspective of the universe, applying to physical, chemical, biological and social realms.

The second edition sub-titled A Big History Perspective features articles from Christian and Chaisson on Big History and Cosmic Evolution respectively. This edition is available for free online here, or you can order a printed version by contacting the Russian publisher (Uchitel) directly.

The second edition sub-titled A Big History Perspective features articles from Christian and Chaisson on Big History and Cosmic Evolution respectively. This edition is available for free online here, or you can order a printed version by contacting the Russian publisher (Uchitel) directly.

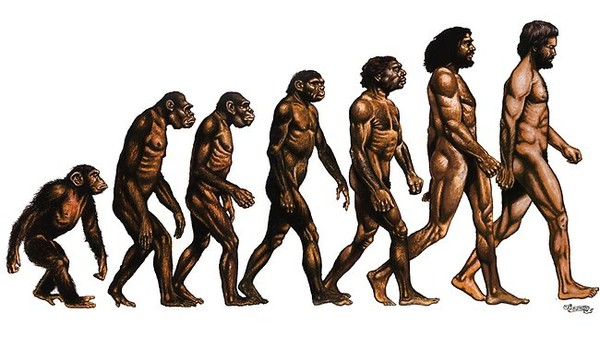

So how did a Great Ape

Lead to people who jape?

Swinging from jungle to concrete jungle

Playing bunga bunga on the drums

Tapping keyboards with our thumbs:

From where, did Homo Sapiens come?

Lead to people who jape?

Swinging from jungle to concrete jungle

Playing bunga bunga on the drums

Tapping keyboards with our thumbs:

From where, did Homo Sapiens come?

There are many books on human evolution; Ian Tattersall's Becoming Human (1998) is very good, and David Christian's Maps of Time (2004) provides a concise summary. However, as this is a rapidly-changing field, the reader may wish to look up something more recent.

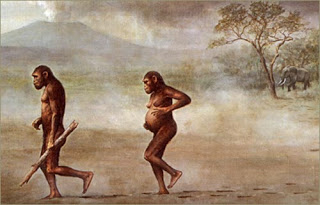

So we had chimpanzees, up trees

Or walking on hands and knees

But great mountains rised

The land dried, forests broke

Grasslands encroached

So we stood up to see

And, hands freed,

Picked up sticks and rocks

And made things we need

Or walking on hands and knees

But great mountains rised

The land dried, forests broke

Grasslands encroached

So we stood up to see

And, hands freed,

Picked up sticks and rocks

And made things we need

An important point of information here is that Homo Sapiens is not a descendant of chimpanzees. We shared a common ancestor with chimpanzees c. 5-7 million years ago, although it would have looked more like a chimpanzee than us.

What follows in this verse is the classic model of human evolution.

What follows in this verse is the classic model of human evolution.

But before I proceed

And you learn by rote

We should note

Another approach

That we diverged on an ancient beach

Diving to reach

Seafood and all that's good

On the shores of yore

Do scientists agree? Maybe. Nearly.

Check it out,

The Aquatic Ape Theory.

And you learn by rote

We should note

Another approach

That we diverged on an ancient beach

Diving to reach

Seafood and all that's good

On the shores of yore

Do scientists agree? Maybe. Nearly.

Check it out,

The Aquatic Ape Theory.

Aquatic Ape Theory is a long-neglected theory proposed by Alistair Hardy in 1960, then championed by Elaine Morgan for decades (e.g. in The Aquatic Ape Hypothesis (1997)), with most anthropologists largely indifferent or dismissive. The topic was the subject of a scientific conference in London in May 2013, indicating that mainstream science might finally be considering it.

Whatever the divergence

Soon came the emergence

Of long-lost cousins, among them

Australopithecus and Homo Erectus

Now Homo Habilis got his hands on this:

The use of tools

Learning, like in school

But where selection rules

Scrape meat from the bone

Don't dine alone

Soon came the emergence

Of long-lost cousins, among them

Australopithecus and Homo Erectus

Now Homo Habilis got his hands on this:

The use of tools

Learning, like in school

But where selection rules

Scrape meat from the bone

Don't dine alone

And I haven't even mentioned

Sexual selection

Trying to get a mate's attention

If you like this song,

Have a dance and sing along

That's how we bond

Sexual selection

Trying to get a mate's attention

If you like this song,

Have a dance and sing along

That's how we bond

Sexual selection is an important force in most of biological evolution: organisms have to survive and reproduce, and to do so they have to choose and be chosen by a mate (or mates). In The Mating Mind (2001), Geoffrey Miller explores sexual selection in general and its impact on the evolution of human intelligence and creativity. Matt Ridley The Red Queen: Sex and the Evolution of Human Nature (1994) is older but also very good.

Tim Birkhead's Promiscuity (2000) surveys the astonishing variety of mating strategies, and their impacts on social and family structures throughout the animal kingdom.

Tim Birkhead's Promiscuity (2000) surveys the astonishing variety of mating strategies, and their impacts on social and family structures throughout the animal kingdom.

Stephen Mithen argues that language evolved in hominids from musical origins in The Singing Neanderthals (2006). William H. McNeill identified communal dance as an instrument of social bonding in human evolution, tendencies which have been utilised by military leaders in the form of drill to form individuals into disciplined, cohesive armies - Keeping Together In Time: Dance and Drill in Human History (1995).

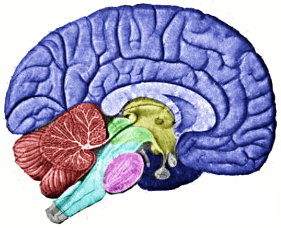

And as our groups grow

It gets harder to know

Who knows who,

Who's high and who's low,

Who I should know…

It's getting so complex

I need more neocortex

It gets harder to know

Who knows who,

Who's high and who's low,

Who I should know…

It's getting so complex

I need more neocortex

Soon the grunts you heard

Became nouns and verbs

String together words

With the art of language

We can manage

Many more techniques

Shared through speech

I can hear new pages turning:

The rise and thrive

Of collective learning

Became nouns and verbs

String together words

With the art of language

We can manage

Many more techniques

Shared through speech

I can hear new pages turning:

The rise and thrive

Of collective learning

And what this will mean

For genes

Remains to be seen…

For genes

Remains to be seen…

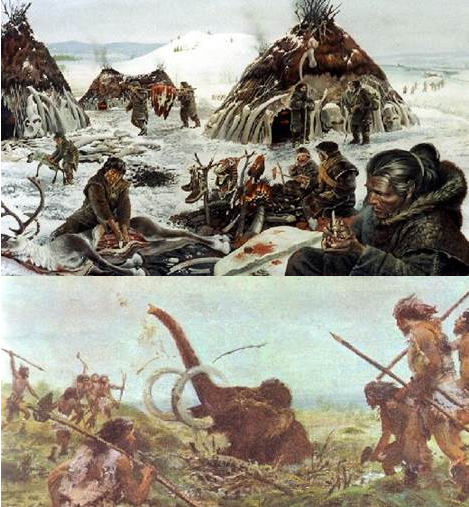

But in the meantime,

Unfazed by Ice Ages

We wandered and wandered

Hunted and gathered

Learnt to make a living

In every climate

On every continent

In every environment

Much to the detriment

Of large animals

That we'd find, and eradicated

By now, humans already dominated

What would become of them?

What would be their fate?

Unfazed by Ice Ages

We wandered and wandered

Hunted and gathered

Learnt to make a living

In every climate

On every continent

In every environment

Much to the detriment

Of large animals

That we'd find, and eradicated

By now, humans already dominated

What would become of them?

What would be their fate?

Stephen Mithen's After the Ice: A Global Human History 20,000-5,000 B.C. (1999) is an entertaining survey of the variety and ingenuity of Neolithic life across the globe written from the first-person perspective of a time-traveller. This is probably as good a book as any to understand ancient hunter-gatherer lifestyles; it also considers humans' first experiments with agriculture and settlements of permanent buildings, which we will meet in Act II.

From as early as c. 40,000 B.C. down to the present, humans have caused the extinction of many large animals (megafauna), some that we are familiar with such as the dodo or woolly mammoth, some less famous such as sabre-toothed marsupial lions in Australia or pygmy elephants on Crete. The importance of human agency in these megafauna extinctions has been contested, with climate changes associated with the end of the Ice Age also blamed. However, current consensus appears to hold that the timing and location of extinction events correlate closely with evidence of human presence and not with climate changes.

Jared Diamond argued this point forcefully in The Rise and Fall of the Third Chimpanzee: How Our Animal Heritage Effects the Way We Live (1991): the recently extinct species had survived at least 3 million years of similar climactic fluctuations associated with the latest regime of glacial-interglacial cycles which Earth has experienced since the closing of the Panama isthmus. Further, species whose territories did not overlap with humans during the latter's evolution would have failed to evolve an extinctive fear of humans (which even African lions have today). This certainly facilitated extinctions in historical times, such as the dodo and other flightless birds of New Zealand, Polynesia and Indian Ocean islands. Personally I think we killed off the biggest animals and the most dangerous (to us), except in hot areas of Africa and Asia where disease may have prevented us from sustaining adequately large populations in the animals' habitats.

Jared Diamond argued this point forcefully in The Rise and Fall of the Third Chimpanzee: How Our Animal Heritage Effects the Way We Live (1991): the recently extinct species had survived at least 3 million years of similar climactic fluctuations associated with the latest regime of glacial-interglacial cycles which Earth has experienced since the closing of the Panama isthmus. Further, species whose territories did not overlap with humans during the latter's evolution would have failed to evolve an extinctive fear of humans (which even African lions have today). This certainly facilitated extinctions in historical times, such as the dodo and other flightless birds of New Zealand, Polynesia and Indian Ocean islands. Personally I think we killed off the biggest animals and the most dangerous (to us), except in hot areas of Africa and Asia where disease may have prevented us from sustaining adequately large populations in the animals' habitats.

--The end of Act I--

Act II - Themes in the History of Civilizations before the Industrial Revolution / Modern Era

Millions of years of natural selection

What's for breakfast

Too many choices to mention

So we'd pick the best ones

Planting seeds in our gardens

Fruits ripen, nuts harden

The human hand guiding nature

A new accelerator

What's for breakfast

Too many choices to mention

So we'd pick the best ones

Planting seeds in our gardens

Fruits ripen, nuts harden

The human hand guiding nature

A new accelerator

Stephen Mithen, After the Ice (1999), mentioned in Act I, is good on humans' experiments with small-scale plant growing long before they became dependent on domestication for sustenance.

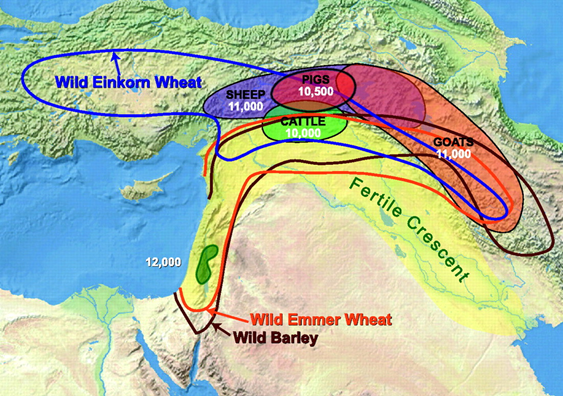

At a continental crossroads in the Middle East

We found wheat and tame sheep

So we sowed and we reaped

Irrigate to hydrate and create

More farmland out of sand

Let's expand!

More and more people in the land

Is it getting out of hand?

We found wheat and tame sheep

So we sowed and we reaped

Irrigate to hydrate and create

More farmland out of sand

Let's expand!

More and more people in the land

Is it getting out of hand?

David Christian's Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History (2004) argues that agriculture and towns first occurred in what is today southern Iraq because it was a crossroads of human trade routes as well of plant and animal species, where various valuable innovations, both human and biological, could accumulate.

When we plant seeds

And pluck weeds

It's something earned

But it's also something learned

New skillz, knowledge

In the global college

Not static but diffusing

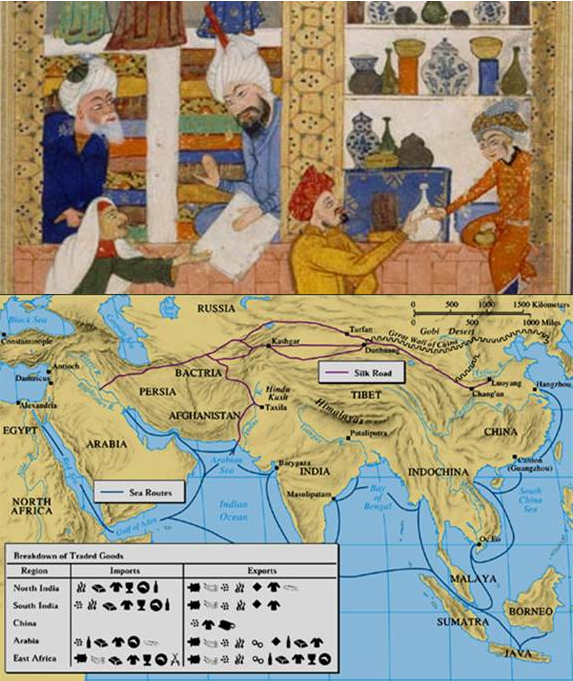

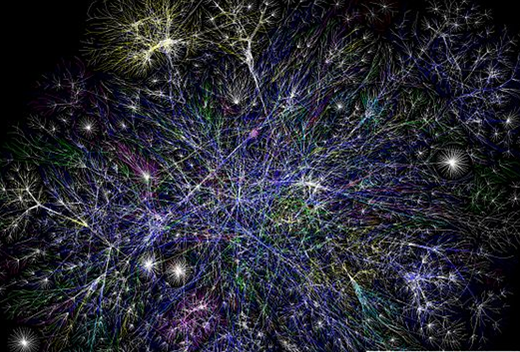

People choosing new things

And moving

Where terrain suits

Travel and trade routes

Can re-distribute

The gains:

Like metals, silks, grains

And all the contents of brains and veins

Interaction and exchange

Drive change with limitless range

Step forward to the stage

The players of every age

Contacts are the threads that spread

To form the Human Web

And pluck weeds

It's something earned

But it's also something learned

New skillz, knowledge

In the global college

Not static but diffusing

People choosing new things

And moving

Where terrain suits

Travel and trade routes

Can re-distribute

The gains:

Like metals, silks, grains

And all the contents of brains and veins

Interaction and exchange

Drive change with limitless range

Step forward to the stage

The players of every age

Contacts are the threads that spread

To form the Human Web

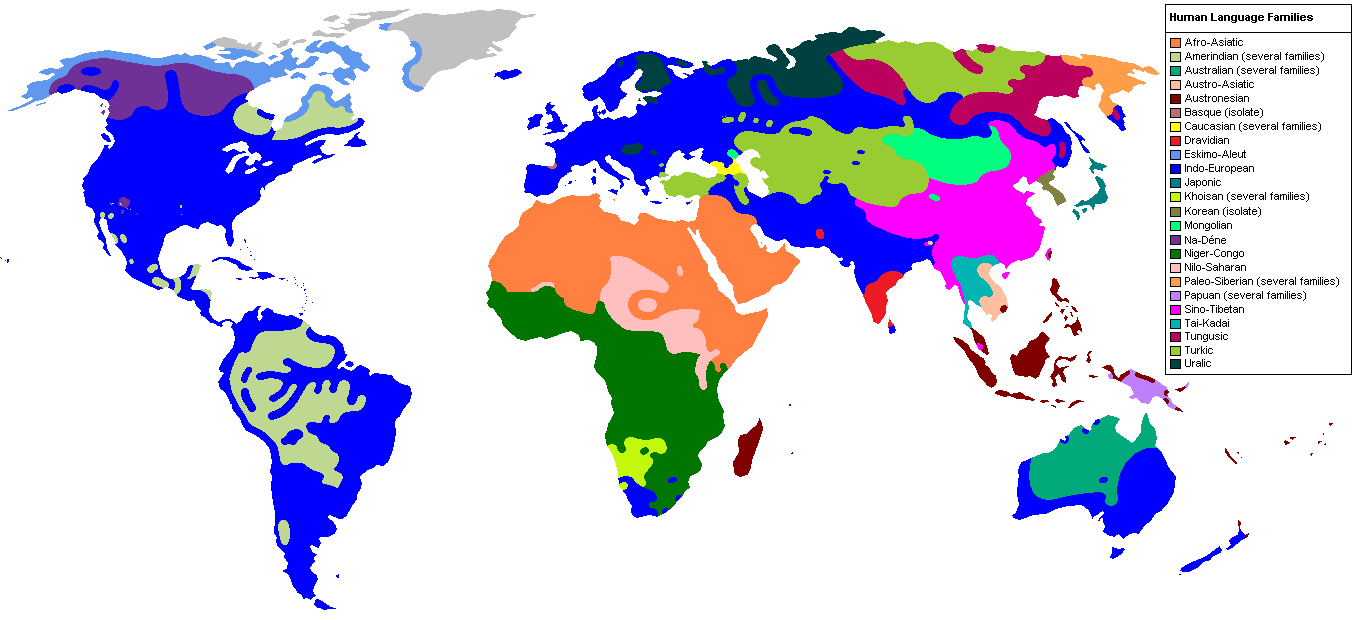

Jared Diamond Guns, Germs and Steel (1997) observes that diffusion was easier across Eurasia than in Africa or the Americas because the 'principal axis' of Eurasia runs west-east, therefore plants and animals, both wild and domesticated, can spread more easily over very large distances in similar climate and environmental conditions. The north-south axes of Africa and especially the Americas permitted less mixing of potentially productive species, and slowed the spread of agriculture and domestication from their sources of origin.

One of the general observations of William H. McNeill in his first magnum opus, The Rise of the West: A History of the Human Community (1963) was that the interaction and borrowing of ideas, techniques, diseases, etc. was a driver of major, perhaps primary, importance in Human history. This was a significant departure from previous attempts to write world history, which tended to focus on the peculiarities of civilizations (and the 'races' that comprised them) to explain their divergent historical paths. So, McNeill's first great contribution to human knowledge was to identify a causal factor which not only offers much greater explanatory power than previous (and many subsequent) attempts to analyse the human past (and present), but also does so in a way that highlights the shared, community aspects of the Human adventure on Earth, which are otherwise easily overlooked. McNeill discusses his initial inspiration here.

Forty years later, McNeill co-authored The Human Web (2003) with his son J.R. McNeill; this work takes McNeill's earlier ideas to their logical conclusion: if interactions are what drives change in the human world, then arguably the central object of study in human history should be the integrated networks, or web, formed by those interactions and the connections that allow them to happen. Note how this idea becomes more powerful in the context of David Christian's concept of gravity forming regions in time and space where interactions become particularly intense and frequent. (Addendum: McNeill himself made a comment to this effect in his 1994 essay, The Changing Shape of World History, which can be read here.)

Forty years later, McNeill co-authored The Human Web (2003) with his son J.R. McNeill; this work takes McNeill's earlier ideas to their logical conclusion: if interactions are what drives change in the human world, then arguably the central object of study in human history should be the integrated networks, or web, formed by those interactions and the connections that allow them to happen. Note how this idea becomes more powerful in the context of David Christian's concept of gravity forming regions in time and space where interactions become particularly intense and frequent. (Addendum: McNeill himself made a comment to this effect in his 1994 essay, The Changing Shape of World History, which can be read here.)

So we built walls, market stalls

Invented deities to stay at ease

They'll help if the rains cease

But as soon as we'd make it

Someone wants to take it

Had to pay our mortal lords

For protection from their swords

Invented deities to stay at ease

They'll help if the rains cease

But as soon as we'd make it

Someone wants to take it

Had to pay our mortal lords

For protection from their swords

Goudsblom, Jones and Mennell co-authored the short work, Human History and Social Process (1989) which contains thought-provoking approaches to various questions that are not normally considered by mainstream historians, such as how priestly and warrior elites emerged, followed by states. I think it was here that the authors argued that states began as protection rackets (not dissimilar to the modern Mafia); I may be wrong as I read this a long time ago at university. (Addendum: I think actually I saw the protection racket origin of the state theory in a book by Charles Tilly, possibly Coercion, Capital and European States, AD 990-1992.)

Uchitel, the publishers of the Evolution journal referenced in Act I, also have an issue entitled The Early State, Its Alternatives and Analogues (2004), by Grinin, Carneiro, Korotayev et al. (eds.); I have not read this yet but it looks fascinating and can be accessed here.

David Christian's Maps of Time (2004) points to the same Middle Eastern crossroads among which early agriculture emerged as fostering the appearance of the first towns and states.

Uchitel, the publishers of the Evolution journal referenced in Act I, also have an issue entitled The Early State, Its Alternatives and Analogues (2004), by Grinin, Carneiro, Korotayev et al. (eds.); I have not read this yet but it looks fascinating and can be accessed here.

David Christian's Maps of Time (2004) points to the same Middle Eastern crossroads among which early agriculture emerged as fostering the appearance of the first towns and states.

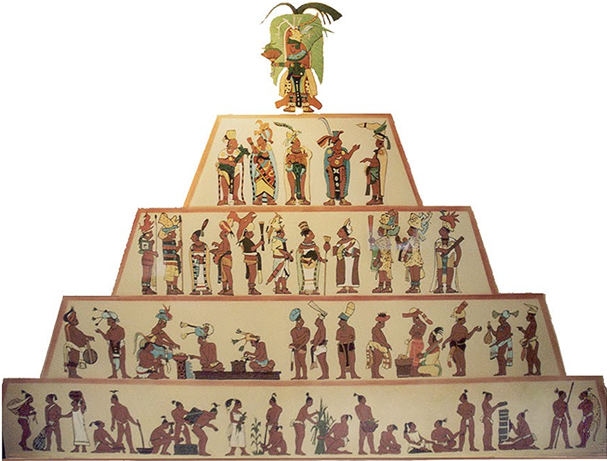

Next we had towns

Men wearing crowns

Handing down

Laws and order

Warriors on the border

Scribes to keep tabs

On what's owned

And who owes

Priests to pray and feast

All supported by the beasts

Of burden

Taking what I'm earning

Men wearing crowns

Handing down

Laws and order

Warriors on the border

Scribes to keep tabs

On what's owned

And who owes

Priests to pray and feast

All supported by the beasts

Of burden

Taking what I'm earning

Ruler after ruler

It began in Ancient Sumer

They'd fall and they rised

Civilizations, and empires

But the basics were the same

For all the Big Names

From Babylon to Sargon

The Hittites are far gone

Shang, Zhou

Qin, Han

Tang, Song,

Yuan, Ming, Qing

Sasanids, Safavids,

Ummayads and Fatimids

Mamluks, Ottomans

Olmecs, Aztecs, Chan Chan to Incas

The basics were the same

For all the Big Names

It began in Ancient Sumer

They'd fall and they rised

Civilizations, and empires

But the basics were the same

For all the Big Names

From Babylon to Sargon

The Hittites are far gone

Shang, Zhou

Qin, Han

Tang, Song,

Yuan, Ming, Qing

Sasanids, Safavids,

Ummayads and Fatimids

Mamluks, Ottomans

Olmecs, Aztecs, Chan Chan to Incas

The basics were the same

For all the Big Names

That said,

We might pause to wonder at

Their intellectual achievements

Technical developments

Theories of the elements

Pyramids on the Nile

Artistic styles

Travelled over

Miles and miles

Canals and compass

Paper and the press

Metaphysical systems

Helped manage duress…

We might pause to wonder at

Their intellectual achievements

Technical developments

Theories of the elements

Pyramids on the Nile

Artistic styles

Travelled over

Miles and miles

Canals and compass

Paper and the press

Metaphysical systems

Helped manage duress…

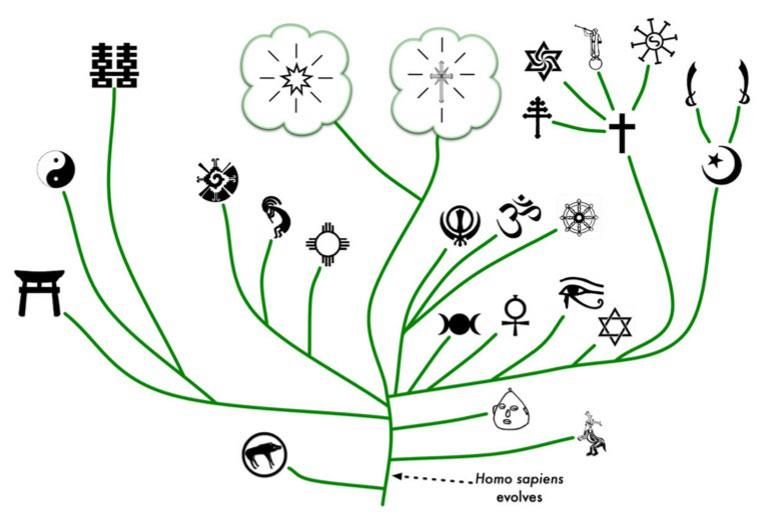

William H. McNeill's The Rise of the West (1963), mentioned above, is probably still the best introduction today on the evolution of art, religion, philosophy and culture in general in human societies. Karen Armstrong's The Great Transformations (2006) on the gradual divergence and evolution of numerous scripture-based religions from simpler Indo-European origins, particularly during the 'Axial Age', is very thorough. Armstrong is more interested in the spiritual aspects of religion than why or how they evolved but there is much detailed content that permits consideration of evolutionary processes. The progression of Yahweh, for example, from a local, ethno-national deity amongst a host of rivals, to the strongest of the gods, to the only god is illuminative.

On a side note, Armstrong's central point is that human enlightenment and spiritual ascendance is achieved by abandoning the ego and all selfish desire and devoting oneself to the service of others, and (crucially) that this has been discovered independently by all the major world religions; this knowledge is a basis for an ethical world universalism.

On a side note, Armstrong's central point is that human enlightenment and spiritual ascendance is achieved by abandoning the ego and all selfish desire and devoting oneself to the service of others, and (crucially) that this has been discovered independently by all the major world religions; this knowledge is a basis for an ethical world universalism.

Being self-aware

We had to stare

At the brutal truth

Of our own mortality

So we'd turn to

Spirituality

Soul-body duality

Helps cope with reality

We had to stare

At the brutal truth

Of our own mortality

So we'd turn to

Spirituality

Soul-body duality

Helps cope with reality

This is the first mention of spirituality or religion, but the reader should be aware this introduction really belongs in Act I - archaeological evidence suggesting some form of spiritual belief has been found all over the world as early as 50,000 years ago - ceremonial burial, artefacts, etc.

And so we got along

Worshipping our pantheons

Local families of gods

Would become obsolete

When new cultures meet

Worshipping our pantheons

Local families of gods

Would become obsolete

When new cultures meet

The arguments here about disruption to belief in the ancient, local pantheons as social horizons widened, particularly when conquered by foreigners, I first read I think in William H. McNeill's A World History (1967). Likewise for the observation that monotheistic belief arose and spread among scattered urban milieus of great Empires with mingled ethnic compositions and difficult, uncertain conditions of life.

A World History is a concise version of Rise of the West (1963), written to accompany the World History course McNeill taught at the University of Chicago. I discovered it by shelf-browsing a library as an undergraduate in 2001 and it became the start of my learning about World History.

A World History is a concise version of Rise of the West (1963), written to accompany the World History course McNeill taught at the University of Chicago. I discovered it by shelf-browsing a library as an undergraduate in 2001 and it became the start of my learning about World History.

Amid social dislocation

I yearn for holy salvation

More sophisticated systems

Of belief and superstition

Roots and branches

Schism and division

Competing monotheisms

Borrowing ideas and themes

Like bacteria sharing genes

Getting into bed with kings and queens

What does it all mean?

Religions… actually evolved

Now, there's a mystery solved!

I yearn for holy salvation

More sophisticated systems

Of belief and superstition

Roots and branches

Schism and division

Competing monotheisms

Borrowing ideas and themes

Like bacteria sharing genes

Getting into bed with kings and queens

What does it all mean?

Religions… actually evolved

Now, there's a mystery solved!

The ideas about religion evolving in a manner not dissimilar to natural selection in biology, and in particular the comparison with lateral gene transfer in bacteria, were I think my own when they first occurred to me, although I don't imagine they would be unusual now. Reading McNeill's discussion of the ancient Middle East in A World History (and later in The Human Web), I was struck by how different aspects of religions were shared among each other, and, following jealous competition, the amalgamations of the most suitable components dominated in the long run (jealousy, or intolerance, is of course an evolved trait of the surviving religions). See also Karen Armstrong's The Great Transformations (2006) mentioned above.

Christianity later transformed itself to facilitate fantastically successful partnerships with the Roman Empire and its successor states, which lasted almost to the present day. Christianity was most often introduced into/imposed on a kingdom by the ruler himself (perhaps after groundwork by missionaries), because it suited the crown's interests.

See also the final verse of Act II, which hints at the role of disease in the history of religion.

Christianity later transformed itself to facilitate fantastically successful partnerships with the Roman Empire and its successor states, which lasted almost to the present day. Christianity was most often introduced into/imposed on a kingdom by the ruler himself (perhaps after groundwork by missionaries), because it suited the crown's interests.

See also the final verse of Act II, which hints at the role of disease in the history of religion.

Back to our story:

The pursuit of power, and glory…

They'd come and they go,

Some fast and some slow:

But castles fall into the sea,

For every dynasty, eventually.

The pursuit of power, and glory…

They'd come and they go,

Some fast and some slow:

But castles fall into the sea,

For every dynasty, eventually.

These lines adapted from Jimi Hendrix, Castles Made of Sand (1967)

Horseback raiders,

Foreign invaders

Were just some of the reasons:

Failure of the seasons

Harvests less than pleasing

Hostile microbes

Fester in the lymph nodes

Plagues and pandemics

Or simple demographics…

Foreign invaders

Were just some of the reasons:

Failure of the seasons

Harvests less than pleasing

Hostile microbes

Fester in the lymph nodes

Plagues and pandemics

Or simple demographics…

…'Cause, when…

Population density

Reaches critical intensity

Put more land to the plow

That's how

We'd make do for now

Conquest adds to the harvest

As long as we're strongest

But there are

Limits of expansion

For village and mansion

Inheritance divided, disunited

Restless are the dispossessed

Social stress and less

Tax to bring

For lord and king

Desperate for revenues

They abuse

Civil war goes viral

Downward spiral

We lament and repent

But violence relents

Only when forces are spent

Population can begin to recover

From one cycle to another

Population density

Reaches critical intensity

Put more land to the plow

That's how

We'd make do for now

Conquest adds to the harvest

As long as we're strongest

But there are

Limits of expansion

For village and mansion

Inheritance divided, disunited

Restless are the dispossessed

Social stress and less

Tax to bring

For lord and king

Desperate for revenues

They abuse

Civil war goes viral

Downward spiral

We lament and repent

But violence relents

Only when forces are spent

Population can begin to recover

From one cycle to another

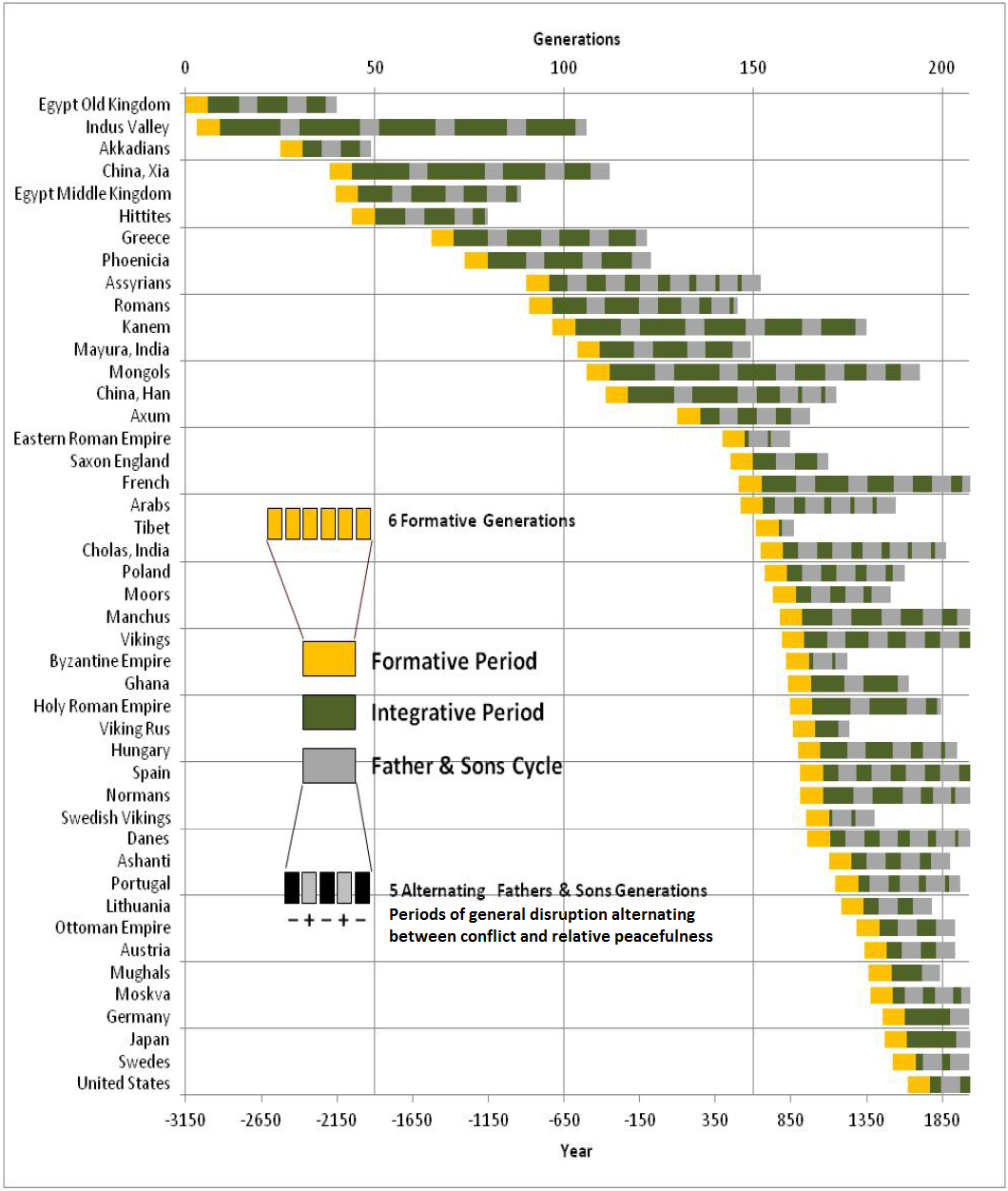

This section describes the major influence of demographic cycles in history, first made prominent by Jack Goldstone's analysis of their importance behind revolutions. Goldstone's ground-breaking work on this topic was titled Revolution and Rebellion in the Early Modern World (1991); a concise preview is available in his article East and West in the Seventeenth Century: Political Crises in Stuart England, Ottoman Turkey, and Ming China, published in Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 30, No. 1 (1988).

Mainstream scholarship has been somewhat slow on the uptake of Goldstone's ideas, although authors such as David Hackett Fischer, The Great Wave (2006), and Gregory Clark, A Farewell to Alms (2008), have written interesting works on the demographic/price cycles and Malthusian forces. Goldstone's pioneering work was finally developed and extended by Turchin and Nefedov, most notably in Secular Cycles (2009) as well as in earlier, more technical works.Turchin and Nefedov expanded the analysis into new realms such as Russia post-1400 and the Roman Empire. They also elaborated the negative impact of conflict on agricultural output (e.g. peasants abandoning fields for the safety of towns), which exacerbated the problems which lead to conflict in the first place.

Peter Turchin also founded (in 2010) and edits the journal Cliodynamics (free online), which is the name he coined in 2003 for the type of historical study discussed here. He provides a concise and illuminating introduction to the concept here.

Mainstream scholarship has been somewhat slow on the uptake of Goldstone's ideas, although authors such as David Hackett Fischer, The Great Wave (2006), and Gregory Clark, A Farewell to Alms (2008), have written interesting works on the demographic/price cycles and Malthusian forces. Goldstone's pioneering work was finally developed and extended by Turchin and Nefedov, most notably in Secular Cycles (2009) as well as in earlier, more technical works.Turchin and Nefedov expanded the analysis into new realms such as Russia post-1400 and the Roman Empire. They also elaborated the negative impact of conflict on agricultural output (e.g. peasants abandoning fields for the safety of towns), which exacerbated the problems which lead to conflict in the first place.

Peter Turchin also founded (in 2010) and edits the journal Cliodynamics (free online), which is the name he coined in 2003 for the type of historical study discussed here. He provides a concise and illuminating introduction to the concept here.

It might not be easy to see

But a civilized economy

Is an ecological entity

Cities living on the surplus

Sun and the soil

Plants grow, men toil

Chopping trees to clear fields,

Increase yields

Soil exposed to wind that blows

Like dust there it goes - oh oh!

Salination or dehydration

Can imperil a whole nation

But a civilized economy

Is an ecological entity

Cities living on the surplus

Sun and the soil

Plants grow, men toil

Chopping trees to clear fields,

Increase yields

Soil exposed to wind that blows

Like dust there it goes - oh oh!

Salination or dehydration

Can imperil a whole nation

But the biggest famines

That we've examined

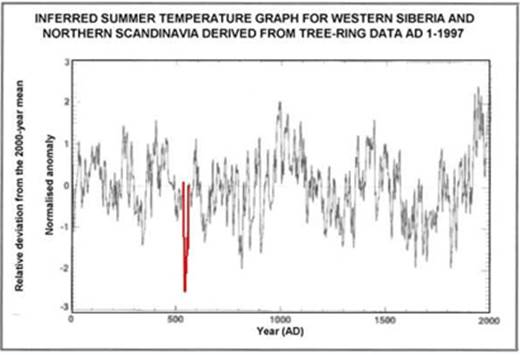

Followed climatic distortions

Of Biblical proportions

Like extreme El Nino

Or super-volcano

No greater destruction

Than mega eruption

Darkened skies

Crops fail, many die

They know not why

But the kingdom, rarely survives

That we've examined

Followed climatic distortions

Of Biblical proportions

Like extreme El Nino

Or super-volcano

No greater destruction

Than mega eruption

Darkened skies

Crops fail, many die

They know not why

But the kingdom, rarely survives

Brian Fagan, Floods, Famines and Emperors (1999) has analysed the impact of various ecological crises on civilizations across the world, including the collapse of ancient Mayan and Khmer Empires, on different sides of the globe. David Keys, Catastrophe (1999), presents a volcanic eruption in between Java and Sumatra as the cause of a year of global cooling in 535 AD, which weakened civilizations all over the world, before unleashing a global pandemic of Black Death which brought many of them to their knees. Amongst other consequences, the collapse of Arabian agriculture, and weakness among the neighbouring Roman and Persian Empires, facilitated the rise of Islam, and its rapid expansion. Keys' work seems to have been largely disregarded until the recent compendium Little (Ed.), Plague and the End of Antiquity (2008), which, while focussing on the plague, mentions and briefly considers Keys' more general argument.

I should also mention a natural phenomenon of destruction which did not make it into this verse (and which would mainly belong to Act I anyway): mega floods caused by retreating ice sheets, when an ice damn collapses and suddenly releases an enormous lake of meltwater that was trapped behind it, e.g. the Missoula Floods, and Agassiz Floods c. 15,000 - 8,000 years ago in North America. The (multiple) Missoula Floods had a peak flow rate c. 1,000,000 times greater than Niagara Falls, at a speed of 80mph. The Missoula dates of 15-13,000 years ago overlap with the older end of the range of estimates for the first human colonization of the Americas; if people were present then the Missoula floods may have been the most dramatic events ever witnessed by Human eyes. Lake Agassiz was larger, and while it's release was possibly less violent, it's disgorge into the North Atlantic is suspected as having shut down the Gulf Stream and caused a 1,000-year hiatus and reversal of the end of the last Ice Age, known as the Younger Dryas. I first read about these epic floods in Doug Macdougall's Frozen Earth: The Once and Future Story of Ice Ages (2004). The cultural memory of similar events in the Middle East, or rising sea levels associated with the end of the Ice Ages, may have inspired the Biblical Flood story.

I should also mention a natural phenomenon of destruction which did not make it into this verse (and which would mainly belong to Act I anyway): mega floods caused by retreating ice sheets, when an ice damn collapses and suddenly releases an enormous lake of meltwater that was trapped behind it, e.g. the Missoula Floods, and Agassiz Floods c. 15,000 - 8,000 years ago in North America. The (multiple) Missoula Floods had a peak flow rate c. 1,000,000 times greater than Niagara Falls, at a speed of 80mph. The Missoula dates of 15-13,000 years ago overlap with the older end of the range of estimates for the first human colonization of the Americas; if people were present then the Missoula floods may have been the most dramatic events ever witnessed by Human eyes. Lake Agassiz was larger, and while it's release was possibly less violent, it's disgorge into the North Atlantic is suspected as having shut down the Gulf Stream and caused a 1,000-year hiatus and reversal of the end of the last Ice Age, known as the Younger Dryas. I first read about these epic floods in Doug Macdougall's Frozen Earth: The Once and Future Story of Ice Ages (2004). The cultural memory of similar events in the Middle East, or rising sea levels associated with the end of the Ice Ages, may have inspired the Biblical Flood story.

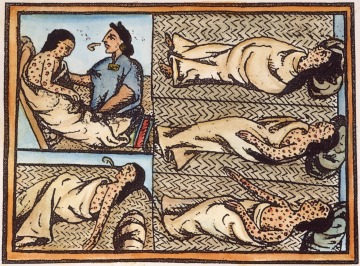

Finally,

What's in a sneeze?

Foreign germs when they breathe

From over land or the seas

Can bring an empire to its knees

Han, Roman, Incas and Aztecs

Conquistadores in Mexico

Deeper in they'd go

Amerindians fell in great waves of plague

Squaws and Braves

50 million died and gave

Emptied lands to the White Man

I raised my palms and I prayed

Are we all to be slaves?

But no answer came

Something's wrong

The gods are all gone.

What's in a sneeze?

Foreign germs when they breathe

From over land or the seas

Can bring an empire to its knees

Han, Roman, Incas and Aztecs

Conquistadores in Mexico

Deeper in they'd go

Amerindians fell in great waves of plague

Squaws and Braves

50 million died and gave

Emptied lands to the White Man

I raised my palms and I prayed

Are we all to be slaves?

But no answer came

Something's wrong

The gods are all gone.

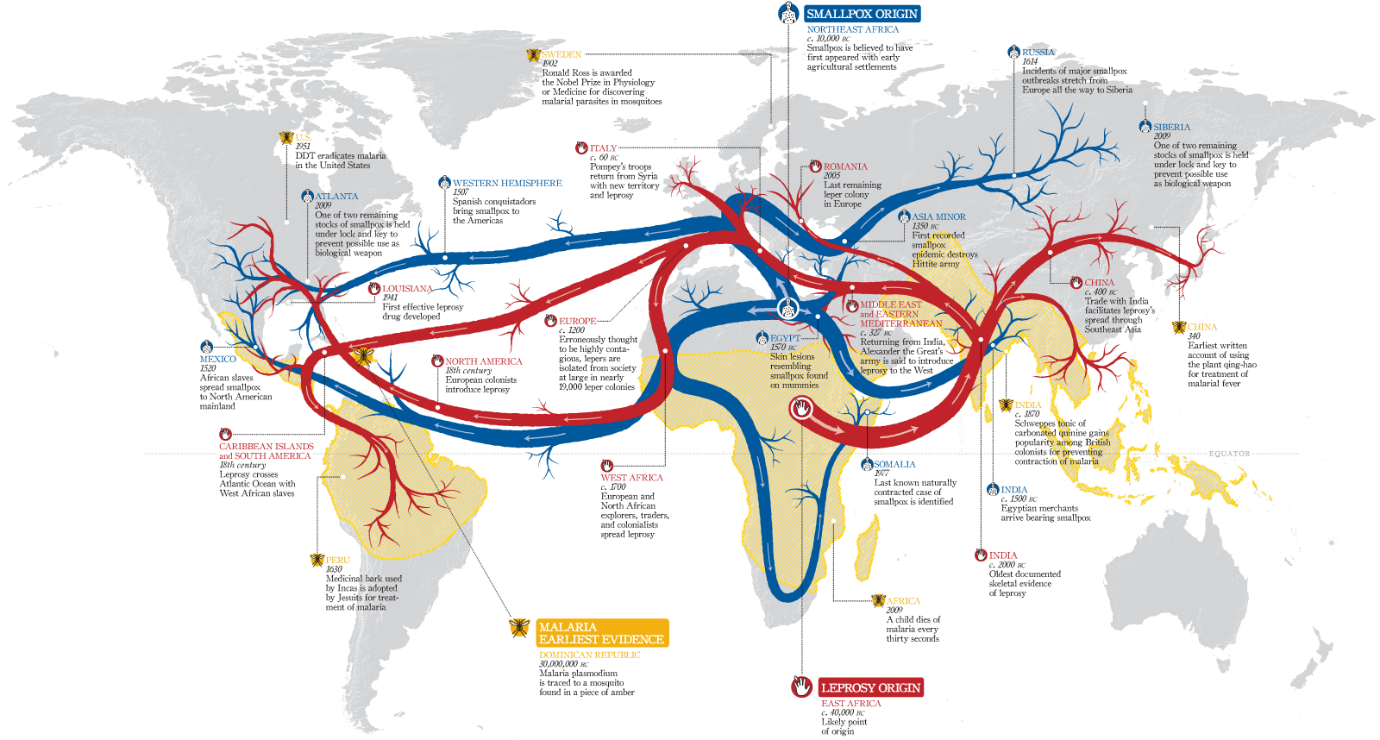

William H. McNeill's Plagues and Peoples (1976) explores the astonishing role of disease throughout history; it was one of the most mind-expanding books I have ever read. Microbes have shaped the fates of societies and empires far more powerfully than any 'great man' or political idea, until medical science brought them under (perhaps temporary) control.

The closing remarks are remarkably prescient, warning about new Asian strains of influenza, and that some 'hitherto obscure parasitic organism may escape its accustomed ecological niche and expose the dense human populations that have become so conspicuous a feature of the earth to some fresh and perchance devastating mortality'. At the time of writing (1976), HIV/AIDS had already spread unknown from West Africa to Haiti and then to the USA and the rest of the world; the pathology would not be successfully identified by American scientists for another ten years.

There are so many powerful ideas in Plagues and Peoples that I will not attempt to do them justice here; but it will be referenced again elsewhere. That it was written by a humanities scholar rather than, say, an equivalent of Joseph Needham trained in the biological sciences, is frankly incredible, and a testament to how far ahead of the rest of academia William H. McNeill was (and still is, for much of it today).

The closing remarks are remarkably prescient, warning about new Asian strains of influenza, and that some 'hitherto obscure parasitic organism may escape its accustomed ecological niche and expose the dense human populations that have become so conspicuous a feature of the earth to some fresh and perchance devastating mortality'. At the time of writing (1976), HIV/AIDS had already spread unknown from West Africa to Haiti and then to the USA and the rest of the world; the pathology would not be successfully identified by American scientists for another ten years.

There are so many powerful ideas in Plagues and Peoples that I will not attempt to do them justice here; but it will be referenced again elsewhere. That it was written by a humanities scholar rather than, say, an equivalent of Joseph Needham trained in the biological sciences, is frankly incredible, and a testament to how far ahead of the rest of academia William H. McNeill was (and still is, for much of it today).

McNeill observed that both native Amerindians and Spanish Conquistadors interpreted the mass plagues that affected the Amerindians but not Spanish as evidence of divine action, and that the subsequent Spanish conquest was divinely ordained. Such interpretations, and the general disruption, disorganisation and loss of morale, as death struck up and down the social hierarchy at will, impeded indigenous resistance.

The role of disease in disrupting religions was not new in history. McNeill argued in Plagues and Peoples (1976) that Christianity made vital inroads in the Roman Empire during the Antonine Plagues (c. 165 AD); Christian charity and willingness to nurse the sick helped save lives and gain converts, while the old gods were discredited by the catastrophe. But forming a powerful symbiotic relationship like that between religion and state can be a double-edged sword: when the Justinian Plagues (540s AD) ravaged the Mediterranean world (and beyond) and, along with the volcanic winter that preceded (and triggered?) them, and decades of ensuing political and social turmoil, the Roman Empire and its religion were again discredited. Thus, the reformist movement known as Islam stepped into the void; or so argues David Keys in Catastrophe (1999).

The role of disease in disrupting religions was not new in history. McNeill argued in Plagues and Peoples (1976) that Christianity made vital inroads in the Roman Empire during the Antonine Plagues (c. 165 AD); Christian charity and willingness to nurse the sick helped save lives and gain converts, while the old gods were discredited by the catastrophe. But forming a powerful symbiotic relationship like that between religion and state can be a double-edged sword: when the Justinian Plagues (540s AD) ravaged the Mediterranean world (and beyond) and, along with the volcanic winter that preceded (and triggered?) them, and decades of ensuing political and social turmoil, the Roman Empire and its religion were again discredited. Thus, the reformist movement known as Islam stepped into the void; or so argues David Keys in Catastrophe (1999).

--The End of Act II--

ACT III - The Rise of the West, Modern Revolutions and the World Today

The web had closed

Around most of the globe

By 1500 AD:

What would the next half-Millennium see?

Primarily

The Rise of the West

From un-cleared forest

To unrestrained behemoth

In just nine centuries

Before cataclysm

And re-balancing

In the process, initiating

Great waves of change

On every continent,

In every domain

The Rise of the West

From un-cleared forest

To unrestrained behemoth

In just nine centuries

Before cataclysm

And re-balancing

In the process, initiating

Great waves of change

On every continent,

In every domain

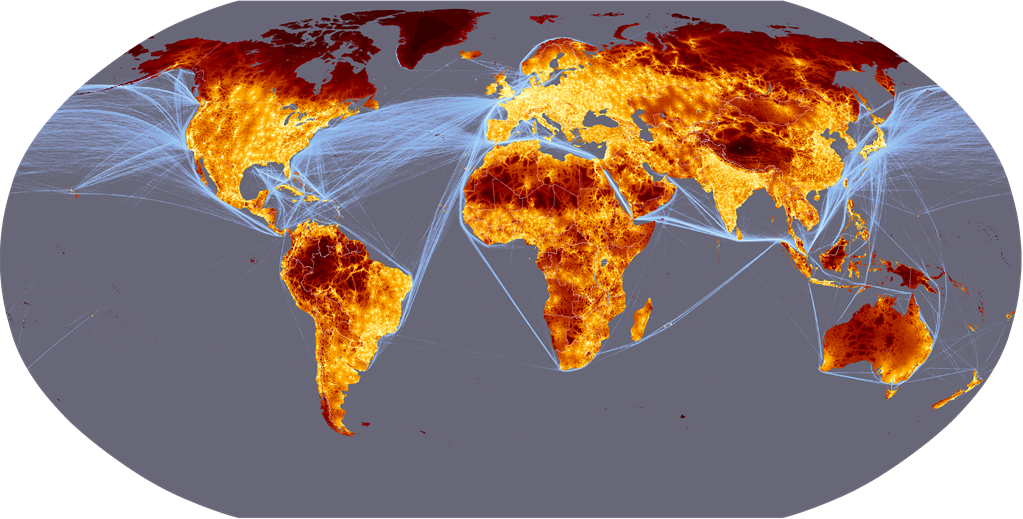

William H. McNeill and J.R. McNeill co-authored The Human Web: A Bird's Eye View of Human History (2003), which we met in Act II, and which follows the progress and impact of the webs of interaction among humans as they spread around the planet. The years around 1500 were an important milestone, not only for the fusion of the Old World and New World webs into the first 'Worldwide Web', but also for the thickening of the webs as long-distance oceanic voyages became more frequent and their cargo more voluminous.

The only exception among complex agricultural societies by this time was the highland region of Papua New Guinea, which was not discovered by outsiders until the 1930s, when aviators observed farmlands there from above.

The only exception among complex agricultural societies by this time was the highland region of Papua New Guinea, which was not discovered by outsiders until the 1930s, when aviators observed farmlands there from above.

'Nine centuries' refers to the period roughly from 1000-1900 AD. Act III picks up the story from c. 1500, when Europe was beginning to 'catch up' with, but was still considerably less sophisticated than, other major Old World civilizations.

So,

Europeans had taken home

The learnings of Rome,

Greece and Islam,

Not to mention

Chinese invention;

Began to expand

Touching every land

From ocean to ocean

Ceaseless motion

Disturbing old notions

Europeans had taken home

The learnings of Rome,

Greece and Islam,

Not to mention

Chinese invention;

Began to expand

Touching every land

From ocean to ocean

Ceaseless motion

Disturbing old notions

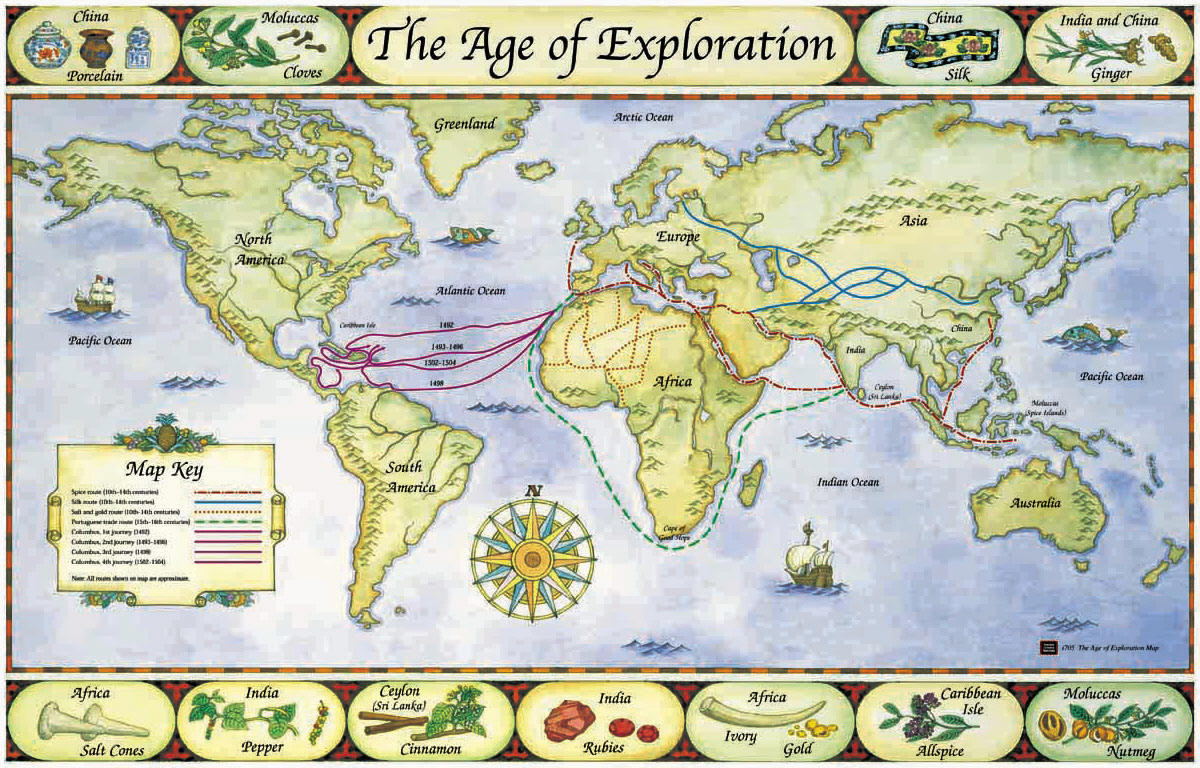

Early in their journeys

They struck

Purely by luck

Two enormous lands

Now called American

Divided by treaties

Full of new species

Numerous peoples

And even some cities

At first through Spain

Came global distribution of the gains,

We called it the Columbian Exchange

They struck

Purely by luck

Two enormous lands

Now called American

Divided by treaties

Full of new species

Numerous peoples

And even some cities

At first through Spain

Came global distribution of the gains,

We called it the Columbian Exchange

William Bernstein's A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World (2008) spends a few concise pages turning the myth of Christopher Columbus as a great navigator on its head. Famously, we are told, Columbus sought a westward route to China, but landed on a Caribbean island instead, inaugurating the discovery of the Americas, which were then unknown to Europeans*. But we might pause for a moment to ask - what would have happened if the Americas were not there? Columbus and his crews would have all starved, lost at sea. And they should have known this - Bernstein explains that the circumference of the Earth had been calculated as long ago as c. 200 BC by the ancient Greeks, with a high degree of accuracy; Columbus cherry-picked his data and deluded himself that the westward route was possible. Unfortunately, the Portuguese royal court was well-stocked with learned men who could check Columbus' maths and point out his fatal errors - that's why he had trouble gaining royal sponsorship! The courts of Spain, England and France also rightly rejected his plans before the Spanish Queen somehow changed her mind. See also James W. Loewen, Lies my Teacher Told Me (1995), for more revision of Columbus myths, including an account of the brutal savagery he meted out on Amerindians.

*'Viking' settlers in Greenland visited Vinland, their name for what is now north-east Canada, once a year to collect supplies especially charcoal, but knowledge of these lands does not appear to have been widespread in Europe, and by 1492 the Greenland colonies were cut off from shipping by the Little Ice Age. In any case, no-one could have guessed that those shores were the edge of two contiguous continents stretching literally to the other end of the Earth. No-one had any clue that there was anything but 12,000 miles of ocean between European and Chinese shores. It could therefore be argued that Columbus' discovery of the Americas was therefore the greatest stroke of fortune in history

*'Viking' settlers in Greenland visited Vinland, their name for what is now north-east Canada, once a year to collect supplies especially charcoal, but knowledge of these lands does not appear to have been widespread in Europe, and by 1492 the Greenland colonies were cut off from shipping by the Little Ice Age. In any case, no-one could have guessed that those shores were the edge of two contiguous continents stretching literally to the other end of the Earth. No-one had any clue that there was anything but 12,000 miles of ocean between European and Chinese shores. It could therefore be argued that Columbus' discovery of the Americas was therefore the greatest stroke of fortune in history

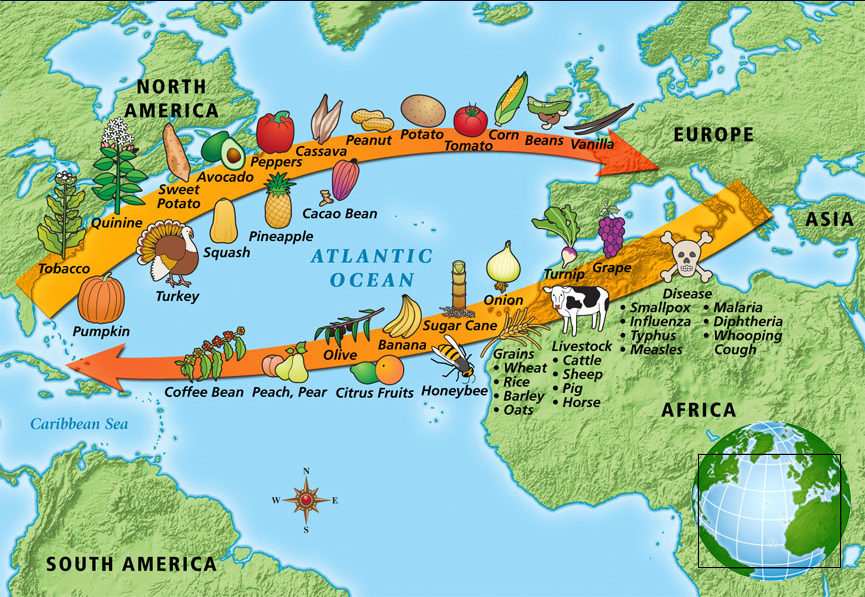

The phrase, 'Columbian Exchange' was first coined by Alfred Crosby in 1972, to describe the enormous range and volume of people, goods, species, techniques, ideas, diseases, etc. which travelled in both directions between the New World and the Old World, over several centuries. William H. McNeill and J.R. McNeill's The Human Web (2003) is of course about interaction in general; the Columbian Exchange followed the fusion of the first fully 'Worldwide Web', to use their terminology, from the existing Old World and New World webs, and is therefore treated at length in its wider context.

I have a copy of, but have not yet read, Charles Mann's 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created (2012), which is the most recent treatment of the subject, but if his 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus (2005) is anything to go by, it will be excellent. 1491 describes the human history of the Americas from the Ice Age colonisation c.15,000 years ago, until the eve of the European intrusion.

I have a copy of, but have not yet read, Charles Mann's 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created (2012), which is the most recent treatment of the subject, but if his 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus (2005) is anything to go by, it will be excellent. 1491 describes the human history of the Americas from the Ice Age colonisation c.15,000 years ago, until the eve of the European intrusion.

Potatoes, tomatoes,

Peanuts chilli and maize

Enriched the diets

Of Afro-Eurasia

Treasures of silver and gold

Helped market trades flow

Medicines, like quinine

To combat malaria

And open all areas

In the other direction

Diseases of course,

Cattle and the horse

Millions of people

The book and the steeple

Peanuts chilli and maize

Enriched the diets

Of Afro-Eurasia

Treasures of silver and gold

Helped market trades flow

Medicines, like quinine

To combat malaria

And open all areas

In the other direction

Diseases of course,

Cattle and the horse

Millions of people

The book and the steeple

The flow of exchange did not happen overnight; many of the important crops took several centuries to take root and flourish in foreign continents. Quinine was exported as a medicine for several centuries before the plants that produced it were themselves exported. Around 1850, plantations of the Cinchon tree, native to Peru and from which the powerful anti-malarial drug quinine is derived, were established in what is now Indonesia. Their output lowered the world price of the drug and finally opened tropical and sub-tropical Africa first to exploration and later conquest; previously the death rate among Europeans was too high to maintain a presence beyond small port communities.

At the end of Act II, we saw how disease devastated indigenous Amerindian peoples, their states and societies, and literally cleared land for white European conquest. But diseases would continue to arrive, including yellow fever and malaria from Africa, which would turn the disease gradient against fresh white European arrivals in widespread areas, particularly the tropics. J. R. McNeill's Mosquito Empires: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620-1914 (2010) is a masterful account of the continuing role of disease in the Americas, from the ecological changes associated with forest clearance and plantation agriculture, which facilitated the spread of the pathogens, to their impacts on political events of the first order.

Ever wonder how the growing naval behemoth that was 18th-Century Great Britain singularly failed to pick off any of the glittering prizes of the declining Spanish Empire? Locally-born citizens of Spanish descent acquired resistance/immunity (or died) in early childhood, so the besiegers of say Cartagena in 1741 would be laid waste while the defenders were not. Meanwhile, black Africans, who enjoyed greater resistance and immunity, were therefore (unfortunately for them) the only reliable source of labour which could work Caribbean sugar plantations once the diseases had established themselves during the 17th-century, greatly increasing demand in the African slave trade.

More surprisingly, the Haitian slave revolt (1790-1804), the American War of Independence (1776-83), the Latin American wars of Independence (1815-20), United States wars against Mexico, and France's failure to build the Panama Canal were all shaped in very significant ways by Yellow Fever and Malaria. Finally, c.1900, the American constructors of the Panama Canal mastered the management of these diseases and their vectors.

Ever wonder how the growing naval behemoth that was 18th-Century Great Britain singularly failed to pick off any of the glittering prizes of the declining Spanish Empire? Locally-born citizens of Spanish descent acquired resistance/immunity (or died) in early childhood, so the besiegers of say Cartagena in 1741 would be laid waste while the defenders were not. Meanwhile, black Africans, who enjoyed greater resistance and immunity, were therefore (unfortunately for them) the only reliable source of labour which could work Caribbean sugar plantations once the diseases had established themselves during the 17th-century, greatly increasing demand in the African slave trade.

More surprisingly, the Haitian slave revolt (1790-1804), the American War of Independence (1776-83), the Latin American wars of Independence (1815-20), United States wars against Mexico, and France's failure to build the Panama Canal were all shaped in very significant ways by Yellow Fever and Malaria. Finally, c.1900, the American constructors of the Panama Canal mastered the management of these diseases and their vectors.

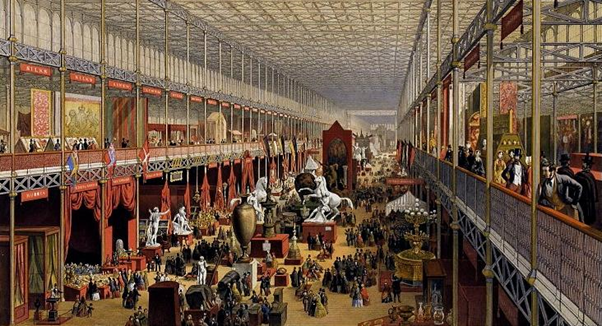

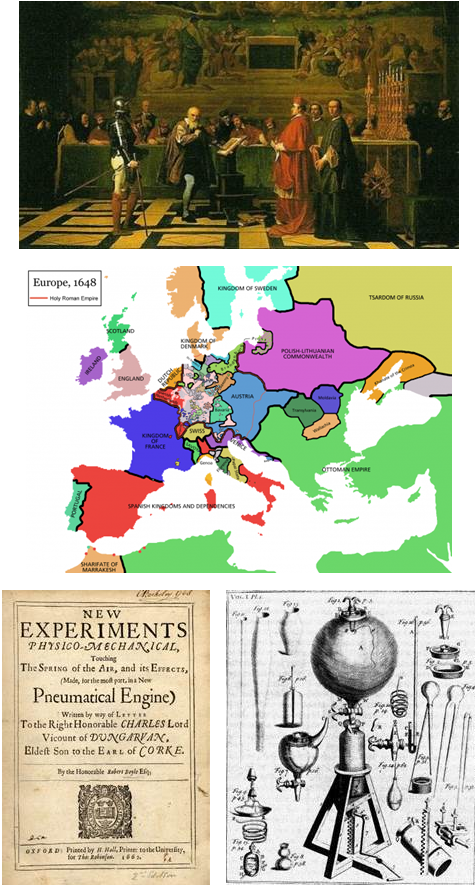

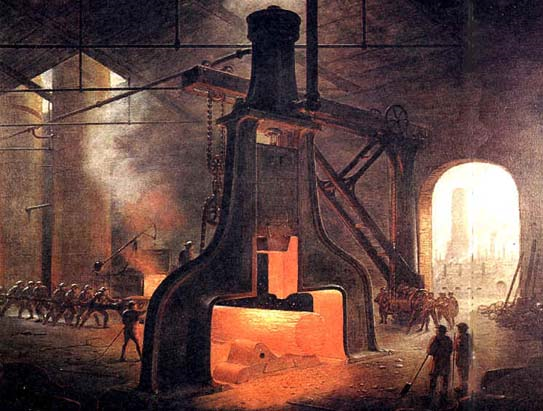

From coast to coast

We're at a crossroads

At the centre of the network

Stood London and Lisbon,

Amsterdam and Antwerp;

Hence the concentration

Of new information

Wealth and innovation

In a narrow location

Canons fired,

What's on the horizon inspired

New phases of evolution:

Scientific, and industrial revolution

We're at a crossroads

At the centre of the network

Stood London and Lisbon,

Amsterdam and Antwerp;

Hence the concentration

Of new information

Wealth and innovation

In a narrow location

Canons fired,

What's on the horizon inspired

New phases of evolution:

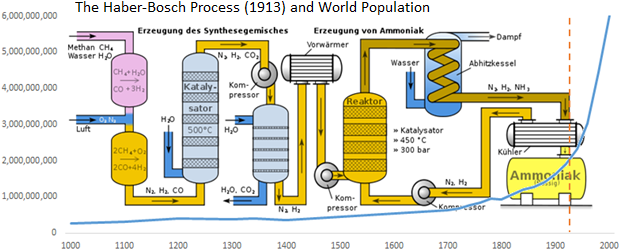

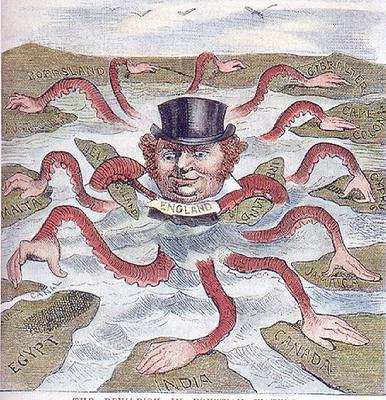

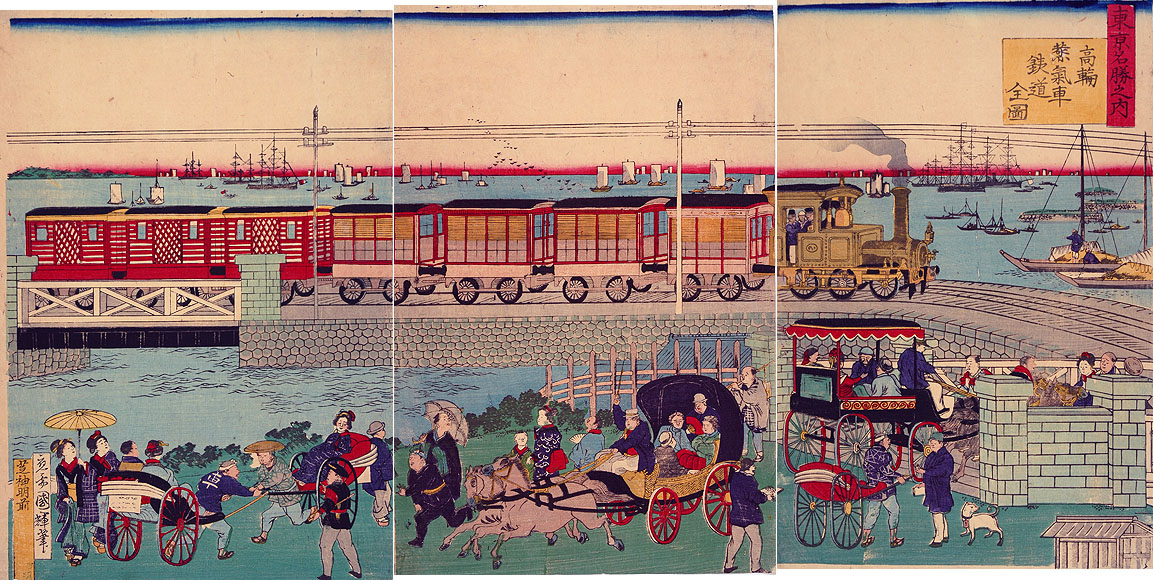

Scientific, and industrial revolution